Years old game titles are no strangers to reflective pieces. Often these pieces talk about legacy, cultural context, or ways the title could have been improved. The PlayStation 1 RPG classic Xenogears is certainly no exception.

Released in 1998, Xenogears was the idea of husband Tetsuya Takahashi and wife Soraya Saga. Originally planned as a concept for Final Fantasy VII and later a sequel to Chrono Trigger, the title had complex themes that Squaresoft thought would be best left as a stand alone title.

Disc 1 featured animated cutscenes, rotatable 3D environments, and a complex battle system. Perhaps most important was the story which contained heavy philosophic and religious undertones that were and by some measures still are mostly unexplored by writing in games today. But the design team for Xenogears was inexperienced and had an incredibly ambitious game ahead of them. Budgetary concerns and a looming deadline forced Tetsuya to make a decision and complete the game as best the team was able. And so it came to be that Disc 2 was created.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of Xenogears is the massive shift in scope and scale from Disc 1 to Disc 2. While Disc 1 features fully playable environments, Disc 2 is told nearly entirely as exposition. Main characters sit on screen while text continues to crawl describing the adventures and stories of the world you were just previously actively exploring. Some dungeons exist, but often in isolation and then are immediately followed by more narration.

One doesn’t have to look hard to find comments to the effect of “The first half of Xenogears was amazing.” The shift to Disc 2 was drastic and once a player knows the development story the purpose behind the shift is easily apparent. Nearly everything about Xenogears changes once Disc 2 begins. Nearly everything – except the story.

While told in a different light, the story does continue. In fact, some of the heaviest and dramatic plot points are revealed in Disc 2. This is the portion of the game where the lore of the world expands in ways that were so challenging for the time it almost caused the game to not be released in North America.

The story is able to stand nearly on its own in Disc 2 because of the way it had to be told. And yet it is “incomplete.”

When viewing the two discs side by side it’s easy to simply label the game as incomplete. It’s plain to see that something changed. To be told of all these amazing places instead of visiting them can definitely cause one to wonder “What if Xenogears was released with a ‘complete’ second disc?”

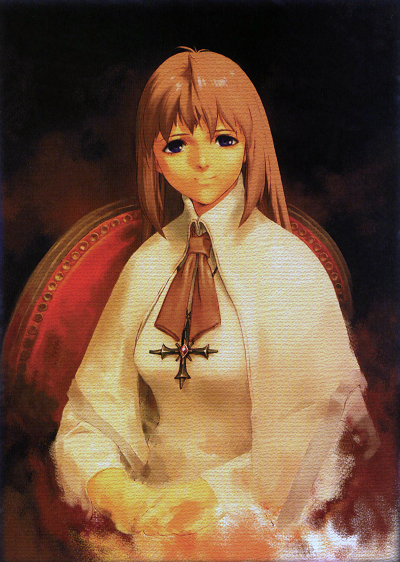

I posted an image from the game a few weeks ago on social media; it’s an in-game painting of Sophia, a leader from a small religious country called Nisan. And the painting is unfinished.

In game the painting is done by Lacan, an artist who doesn’t want his time with Sophia to come to an end. As such he purposely slows down his painting and makes up stories about needing more supplies. The painting is never completed as she eventually sacrifices herself for her people and becomes a legendary figure in the world’s history.

But the painting lives on, incomplete but still revered by those who view it.

The post spurred some conversation with a friend and the topic of a recreated or remastered Xenogears being hypothetically released came up during the discussion. Despite being a favorite title, I wasn’t sure I wanted to see more of Xenogears.

There’s a certain something magical about everything in the game, from the music to the story to the development itself. It’s a coming together of countless passions and accidents and despite it being “incomplete” still holds a formidable place in gaming history. Would “finishing” Xenogears rob it of some of that identity?

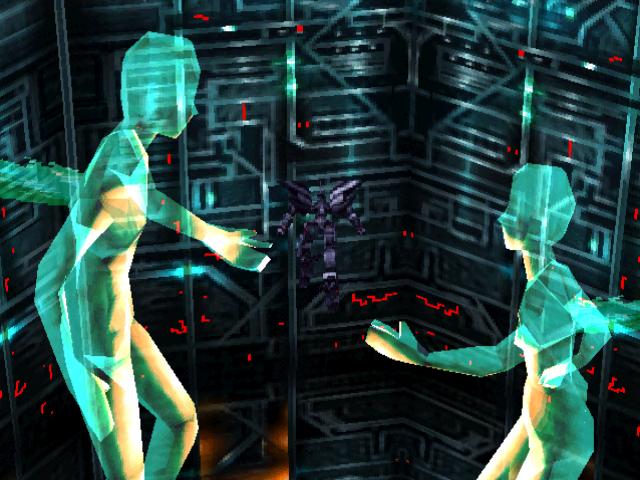

There’s a pair of statues seen in the game, one set in a cathedral and later that same pair in a late game dungeon. The statues are two angels, each with a single wing. When the player first encounters them it’s revealed that these statues are meant to show the power of harmony. By holding the hand of the other the two angels are able to fly by beating their wings as one.

The angels by themselves are incomplete, but with the help of the other they can both soar.

This, I think, is the most important lesson to take from Xenogears. It presents itself as an incomplete and flawed creation. It came from inexperienced people who came together to make something that was beyond their reach to fully realize. And it asks the player to take its hand and lift it up so that both can be lifted in return.

Few things in life are given or experienced in complete and ideal packages. Constant comparison and the asking of “what if?” can be a positive distraction but it also can rob people of the experience in front of them. Additionally, many of the answers to “what if?” hold outcomes that people may not truly want. Would Xenogears still be Xenogears if it were completed today, decades separated from that small team in a 1990s Squaresoft office trying to create something completely new?

Xenogears would perhaps be a better game if it were finished. But it wouldn’t be the game that’s spurred so much devotion since its release. It wouldn’t have that mystique that seems to seep into the very story of the game itself. And it certainly wouldn’t be able to teach players that imperfection is not only okay, but something worth admiration.

Images from xenosaga.fandom.com and lparchive.org