Adios unavoidably deals with depression, self-harm, and suicide. Please be mindful of this if you decide to either play the game or read this review.

Subjective:

Who gets to decide when things are over? How much control do we really have? What use is a crisis of conscience if it eliminates all possibility of future good? These, and many more questions are asked via the first-person discussion and exploration game Adios, presented for review by combo developer / publisher Mischief.

Objective:

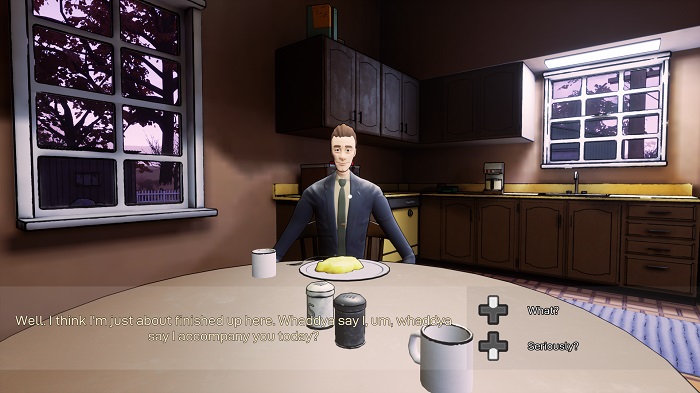

Adios is a single-player only title. It takes advantage of the Unreal Engine to create a farmland for the player to explore. The game progresses as the player completes various chores marked on the map with waypoints. At each waypoint, context-specific controls allow the player to finish the chore and pick various verbal responses to the conversation at hand. Time skips forward after completing each chore and subsequent conversation, and the player is able to decide how they want to spend their time before facing the endgame.

Assessment:

I don’t particularly buy into the notion that videogames are a power fantasy or a means of escaping reality. There is no escape from reality, and I don’t like people doing disservice to what makes them happy or fulfilled by saying that they are. But if I did buy into that notion, then Adios might be the sort of game that would come out of my existence. It’s a brutal fantasy where the empowerment comes not from saving the world, or beating the bad guy, or any other number of standby game win states. The fantasy of Adios is that I might be able to say goodbye on terms I dictate, with someone who is sympathetic, and people who would be sad to see me go.

This is a fantasy for older or more weathered folks, told in a manner which is almost unbearably lonely at times. Developer Mischief utilizes the Unreal Engine to model a farm from a perspective that’s not quite fish-eye but constantly distorts from what we’d consider a traditional view. The emptiness of the home, the long patches of grass between walks, and the way furniture seems far too long suggests a space that used to have life and is now distorted in its absence. The walks between waypoints took an eternity, not because of boredom, but because of the pressure of absent life making each step a personal choice to move through this sad space.

The character designs, all two of them, are as strange and lonely as the environment surrounding them. Both my longtime friend and his partner have eerily elongated limbs to keep me at a distance. Their faces seem so far away even when, in the space of the game, the models are maybe one or two steps away from my current location. Even if I close the distance their bodies seem so far away. That makes the single moment of connection I had in my playthrough that much more meaningful. My friend reached their gangly arm out through this lonely space, grabbed my shoulder, and for those sentences the loneliness faded away in connection. That moment felt so real that the weight of all the alienating touches crumbled in on me at once.

What both my digital self and friend are dancing around in conversation boils down to suicide by cop. It’s implied heavily in the dialogue (and unfortunately spelled out explicitly in the product description) that my friend is part of a mafia which will kill me if I remove myself from its service. The cops and mafia serve the same public and private function – to maintain order for primarily private financial interests and eliminate anyone who disrupts that order. By choosing to step away from this line of work I am also choosing to disrupt this order. So I am making the choice to be killed. I won’t get the dignity of deciding when things are over on my own terms, all I can do is lightly dictate the timeline.

This is what’s being addressed in the branching dialogue and individual choice. My digital friend and I both recognize my death is required to maintain financial order, but he wants to extend that time and I want to make peace with what little time I have left. Therein lay the fantasy of videogames filtered through the brutal reality I’ve seen play out time and again over decades. At least my digital self has the illusion of dictating the terms they get to go out on. I have a feeling my physical end would be considerably slower and more painful if I made the same choice to stop.

Adios was reviewed using a reviewer-gifted code on the PC.

The Review

Adios

There are no perfect games, but there are experiences which completely encapsulate what it means to exist in a moment of time. Adios captures the moment I, and many others, exist in with incredible artistry and mercy.

PROS

- Beautifully, and painfully, recontextualizes what it means to play in a digital space.

- Evironmental details and character designs combine into a unique feeling of loneliness which makes moments of connection that much more impactful.

- Masterful vocal performances which emphasize unspoken pain and longing rather than clean exposition.

CONS

- Having to listen to or read the thoughts of people who insist Adios isn't a game.