Spoiler and trigger warning: this piece will have minor spoilers for Outer Wilds as well as frankly discussing my history of mental health, trauma, and abuse.

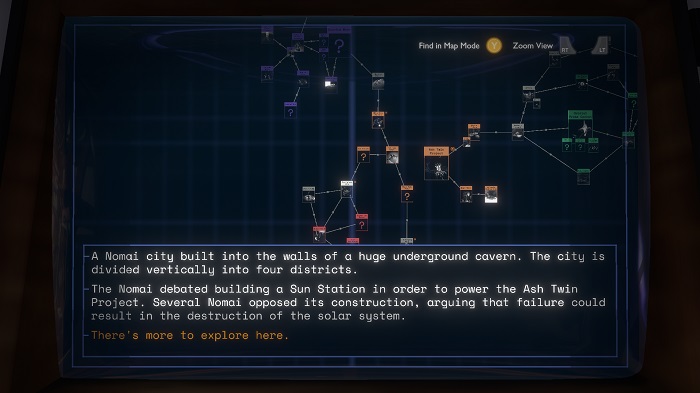

Outer Wilds is a game released in 2019 where you are a space traveler set to go on their first expedition and every 22 minutes their solar system comes to a catastrophic end as the sun goes supernova. There’s no avoiding it and there are plenty of ways to die exploring the multiple planets that hide their own mysteries. Once either your character or the solar system dies the game starts over and it’s up to you to figure out what’s happening between each mortal cycle. It’s also a game where I went from joy to healthy curiosity to disgust to indulging in my paralyzing depression.

How?

I don’t know when the shift took place but as I went through my 50+ cycle I realized I had not been well playing Outer Wilds. The first few times through were filled with tiny delights as I ate marshmallows, messed around with the toy lander, and played hide-and-seek with the kids that populate the starting village. As I revealed the mysteries the joy was replaced with anger at the different characters. The universe is ending, the sun is going to explode, and I can’t get any of you to care. One of my fellow explorers seems like the perfect candidate to become my partner in investigating the cycle, but they’ve given up and are fine just playing their instrument as the world explodes around them. It’s about this point the crushing realization that this finely crafted universe is thoroughly indifferent set in. So why get up? Don’t bother, I’m just going to get up in the same spot, staring at the exact same hint of the destruction to come, and try in vain to make sense of this universe before I die. Again.

This is not a good place for me to be in. Earlier this year my left kidney developed an obstructing stone needing surgery for the third time. A month later my right did the same. On top of the pain of having two obstructed kidneys, I found out my insurance wasn’t going to cover any procedures and left me on the hook for a $60k bill for surgery I wasn’t even able to have because of a change that occurred on the operating room table. Then the lack of coverage led to me being unable to secure my psychological meds, a trip to my psychologist was a disaster, and at some point I just didn’t want to be alive anymore. I’m not suicidal as I didn’t want to be dead, but the distance between not wanting to be alive and becoming suicidal is so slight that I became acutely aware of the unstable precipice I stood on. So when I’m playing Outer Wilds I’ll sometimes get a too-direct reminder of how tenuous the hold on myself can be like – say – when I’m on a hastily assembled platform suspended above a black hole that can collapse if I’m not careful.

Recognizing my depression in the sometimes unbearable loops of Outer Wilds is nothing new. It’s depression. Ever since I was diagnosed it’s been a struggle to not see depression in everything. But finding mental health parallels to video games is becoming increasingly well worn ground for critics to traverse, myself included. I’ve discussed how I saw too much of my abuse in Night in the Woods when Angus talks about his childhood, NakeyJakey is one of many who talked about how Dark Souls pulled him from his depression, Leonardo Da Sidci has a remarkable discussion of his experience with psychosis and Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. We also recently covered the story when NAMI teamed with Twitch for mental health awareness month. Gaming can be an inescapable well of realization that our avatars, digital actions, and connections are safe spaces to explore individual trauma while reminding others they’re not alone.

This isn’t treatment. It’s group therapy, in its own way, and with its own set of benefits and drawbacks. Gaming organizations like RPG Limit Break have helped mental health foundations like National Alliance on Mental Illness continue my generation’s work on destigmatizing mental health challenges. What I’m concerned about is the extent to which description replaces action while leaving ourselves isolated in the digital ether. Take the case of using video games to treat combat PTSD victims. This is a macro good, but more specifically involves continuing to champion military uses of technology that help create the PTSD victim to begin with. So we’re struggling to be heard in a sea of monetized spaces – YouTube, Twitch, even my own website – that benefit from our increasingly exposed pains which could pull the plug at any moment. All the description in the world won’t help if we don’t use these spaces to build a framework of mental health policy and treatment and not just let people know they’re not alone in-between digital Twitch ad breaks.

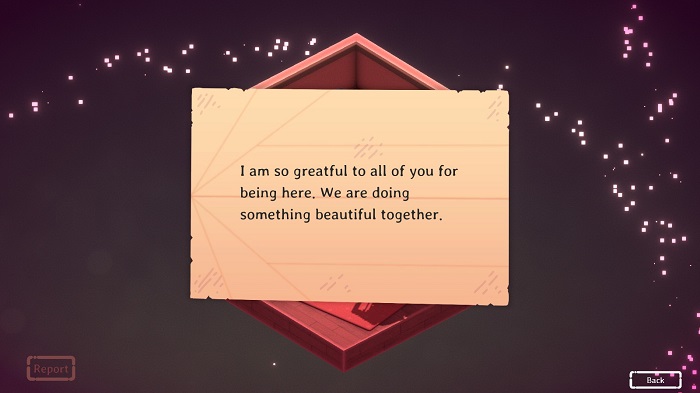

This is why a game like Kind Words (lo fi chill beats to write to) (shortened to Kind Words moving on) is a step toward connecting players in a way the nature of our digital platforms keeps us separated. Kind Words is also a game released in 2019. It provides a soothing electronica soundtrack, tidy room, various decorations, and helpful talking deer to write letters to other players of the game. Think of it like a multiplayer wellness game where the goal is to try and make yourself feel better while hopefully making others feel better by sharing your frustrations, writing out letters of support to others, and just create nice things to send out in the form of paper airplanes. Your reward consists of digital stickers which double as cute in-game decorations.

There’s still problems with this approach. It needs to be heavily moderated in order to keep the focus on mutual uplift and might sound more like an advertisement or shallow positioning about “hacking” mental health (one example here). Using apps and games as therapy has its own dubious value as well and can easily fall into the McMindfulness framework of making problems manageable insofar as they make the user productive to private industry. Combine these factors with how entrenched existing mental health outreach within gaming is with monetized streaming services, and we’ve got reason to be concerned about any game, program, or digital service that offers shaky prescription to a world filled with mental illness and few safety nets.

All that said, Kind Words is kind of saving my life right now. A few months back, I wrote about my year of being sexually abused and the failure of the safety nets I thought were supposed to protect me. While it felt liberating to finally get some of, not all, my abuse out in a record for others to see I also felt the zest for writing completely go out of me. Except for my writing here at Doctors of Gaming, I haven’t had any love for what I dedicated the last decade of my life to. Except when I’m playing Kind Words.

Kind Words is thoughtfully structured. It reminds me time and again that I can’t fix people. I have a problem trying to fix people. The various reminders to watch my mental health and helpful suggestions about what to write keep me in a space where I’m building myself up by building up others. The music is crucial to this overall affect by never elevating the tension of the experience and only serving to keep the fingers typing away in a state of peaceful flow. In the hands of folks obsessed with apps or “hacking” mental health I’d get annoying reminders of how Kind Words is redefining how we discuss mindfulness or depression. Instead, in the hands of careful developers, it’s a genuinely safe space to connect with other people who are in pain and lack an outlet to make things better.

Waking up to the same view of destruction in Outer Wilds isn’t so far removed from the welcoming blank canvas of Kind Words. The former opens up a wealth of metaphorical and descriptive possibilities about the experiences of isolated gamers through an elaborate life cycle of a doomed universe. The latter allows for a guided tour into our individual universes in a safe and supporting manner by offering one prescriptive approach to staving off loneliness, depression, or whatever is bothering me that day. Critically examining Outer Wilds and playing Kind Words are two more breaches into the wider discussion on mental health my generation’s been uniquely positioned to influence. We can’t abandon the subjective descriptive discussions of the former to flood the market with carefully constructed prescriptions of the latter.

Together, we can sharpen our critical lens while creating art that makes connecting with each other less of a depressing struggle. Maybe in 20 years time my brother’s children won’t need to make videos about why a certain game made them feel less alone, and they can instead play a different game that lets them share those feelings in a new way.

Comments 1