Subjective:

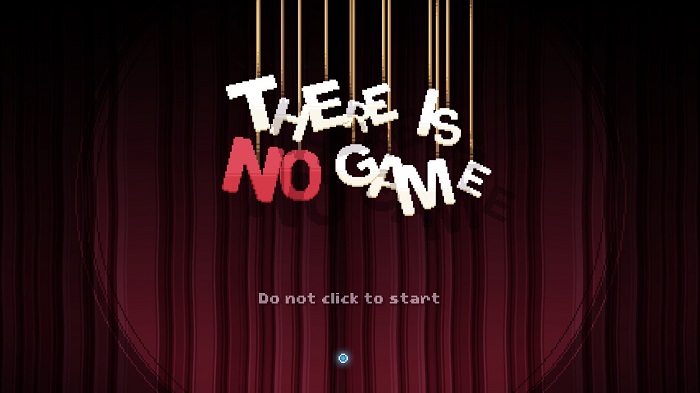

Draw Me A Pixel, acting as developer and publisher, presents There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension (shortened to TING from this point on) for review. TING was birthed from the unsuccessful Kickstarter for, well, itself. As a product which should not be, the developer does not ask the player to come along as it tries to keep people away. Should the player persist in clicking, they may not find humor, explorations of differing point & click genres, and destroy the reason to create art. It may also negate all those aspects, creating a positive, and TING might welcome your input by the end.

Objective:

TING advances as a unique sort of 2nd-person take on different types of point & click adventure games. It presents a road block, such as a board nailed-up over the start of the game, and requires creative thinking from the player to proceed. So the player is less directing the action through their actions as they are effecting the environment in such a way to allow the characters within to proceed. A variety of audio and visual clues, some pulled from the earliest days of cinema and adventure gaming, guide the player along. If the contextual clues are not enough, TING includes a gradual hint system which starts vague then will provide a direct answer if needed.

Assessment:

A quick way to my heart is to both utilize and understand the appeal of Buster Keaton – the silent film genius of early cinema. TING, to its enormous credit, gets that Buster’s appeal was not in the slapstick violence (which inspired the more annoying 3 Stooges) but in Buster’s dogged determination throughout each cinematic ordeal. The player both assumes and guides a Buster-type character in TING, having to think creatively to guide an unwilling protagonist to their triumphant destiny.

The philosophical drive of TING might be rooted in Buster, but the gameplay is a loving tour through the history of point & click adventure games. It illustrates how the genre started with abstract thinking over concrete situations and how that abstract thinking evolved into onscreen avatar manipulation. Additionally, it also demonstrates how we’ve made ourselves an inevitable part of the gaming creation process. In this manner, TING manages to explain how video games are not an escape from reality but rather can be a dive into the self. This sounds lofty, which is part of why I enjoyed it so much, but TING manages to make this point with a brisk sense of joy and not with self-seriousness or cynically detached humor.

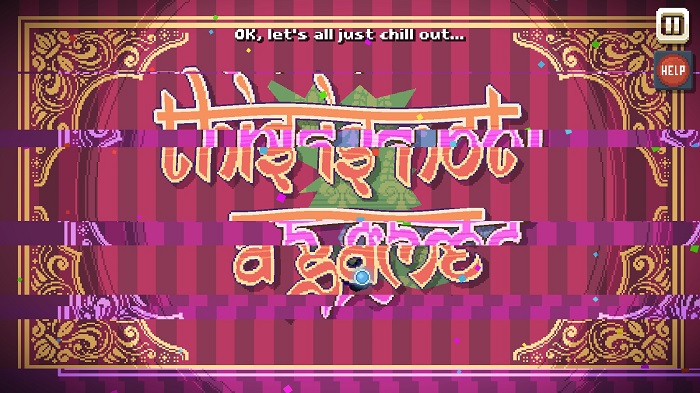

Not that TING is lacking critical targets. Its best section, in terms of genre criticism, takes direct aim at free-to-play video games and the bevy of roadblocks developers put in to ensure players get snagged in purchases. This had the potential to become the very thing it was criticizing as quite a few clicks are needed to navigate the hero within the game within the not game of the game of TING (I rarely get to write descriptive sentences like this). Then, in the midst of a clicking frenzy, I got a notification for an achievement that I’d clicked far more than I needed to. TING both got that gamer drive to over-accomplish, which resulted in my overboard clicking, and also managed to be a reminder that – hey – this is a game and I’ve done what I need to move on. So why not move on together?

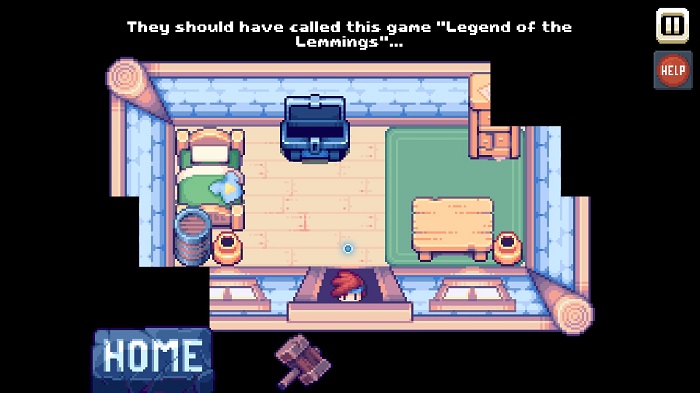

Moving on takes us through a tour of some expected artistic styles like that of LucasArts’ golden era of adventure gaming. Those moments are lovingly recreated in the jagged cartoonish edge that sits warmly in the nostalgia of many. What I wasn’t expecting was the ode to behavior teaching adventure games like Wonder Project J. This led to some surprisingly deep laughs as I shared the narrator’s frustration with the section’s protagonist at behavior I could have predicted had I followed strict in-genre logic to its natural conclusion. That Draw Me A Pixel managed to utilize, critique, and nudge away from adventure game moon logic is a massive credit to TING‘s deft touch.

TING doesn’t entirely do away with some of the nagging aspects of its self-aware nature. Puzzling through some sections led to narration hints which repeated far too often, adding a rare bit of actual old-school adventure game annoyance to the meta pile (the similarly self-aware Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy at least had a narrator who knew when to scoot aside for a while). It also does not change that there is a touch of moon logic to a handful of puzzles. Moon logic, even taken at self-aware humor value, continues to be an aspect of adventure gaming which will turn off player who just want to complete the darn thing.

There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension was reviewed using a reader-provided code of the game through the PC Steam service.

The Review

There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension

Even with those minor quibbles, There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension exemplifies the joys of a self-aware genre exercise that goes beyond knowing replication. This experience can sit comfortably next to similar moments of self-aware greatness such as "Duck Amock" or, to keep it in video games, the narration of the Space Quest series. It's a great rejection of cynicism and shows how much joy there is to be gained by reveling in our shared knowledge of video games, not drowning in it.

PROS

- Loving tour through multiple decades of adventure games and art history.

- Self-referential perspective still values the player's time, never indulging in tropes for the sake of it, and gently affirms progress.

- Breezy presentation with warm sprites and some surprisingly effective slapstick FMV comedy.

CONS

- There are still repetitious adventure gaming segments and a bit of moon logic that even stretches those sympathetic to the game's approach.