Subjective:

Developer and producer Finji present the isometric tactical survival game Overland. The player gives commands to a survivor of an apocalyptic invasion of spiny creatures. It is possible to grow the crew from one to many while navigating the land from East to West coast.

Objective:

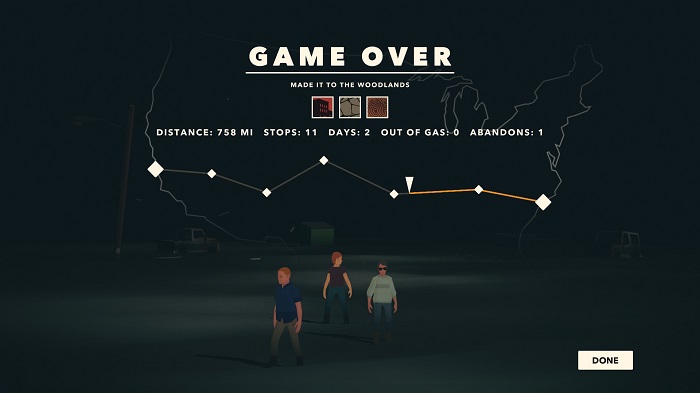

The goal of Overland is to escape each scenario map with at least one survivor, and in-between each scenario map the player may pick a destination that may have supplies, potential companions, or environmental flavor. With the exception of picking up and dropping items, Overland functions on a turn-based system where each action takes a bit of stamina. The survivors the player may guide are randomized each playthrough, and some have greater stamina while make more noise, or may use tools with a lessened chance for wear-and-tear. There are personality details as well that function primarily as a descriptor but also have a little weight on the banter between survivors. Dogs may be recruited, but they essentially function as less verbose athletic humans. As the player progresses further, clues are laid out surrounding the invasion.

Assessment:

It frustrates me when games seem unable to commit to a single tone. When that inability to commit to a single tone gets stretched to each facet of its presentation it becomes more bewildering that frustrating. Overland is an apocalyptic story with disconnected dialogue, personality traits that don’t affect much, and generic bulbous character designs that blend one character into the next. It also features a roguelike system that only changes the starting point instead of the overall gameplay. All these aspects needed to be fleshed out, but if any aspect was fleshed out it would necessitate a new game experience, so each bit of dissatisfaction almost requires the next in order for Overland to work at all.

Let’s start with the core loop of surviving each map. The player’s characters, randomized each playthrough, must use stamina for each action on the map. This excludes picking up or putting down items, which can lead to odd situations where your character can’t make that extra foot jump to escape a creature but can pick up five gallons of gas, switch it out with a wood palette, and repeat the action as much as the player can stomach. It’s amusing for a while, but with the lightly somber tone of Overland this stands as a poorly thought out omission. Each action matters, except when the player decides to juggle inventory in lieu of continuing to survive each map scenario.

Except for the juggling, it’s a puzzling good time to figure out how to get through each map with the most resources and survivors possible. I enjoy that mechanics have to be intuited from each run instead of outright explained, even if that leads to odd scenarios like the previously mentioned inventory juggling. The best moments involve figuring out the relationships between each kind of spiny creature. In the beginning, killing one summons others, and I thought the same would apply to the deer-like red creature that appears later. When I was forced to kill one, to my surprise, it didn’t summon another. This puzzled me until I remembered instances of the red creature killing the blues to get to me. Predators of my predators aren’t my friends, but at least I could manipulate their relationship to one another to efficiently clear a path ahead.

The rest of Overland is disconnected from all other aspects of itself. The bulbous and lightly homogeneous character models suggest a struggle with identity, but the writing makes sure to explain characters with names and a bit about their backstory. These backstories barely affect each character’s ability to carry out different actions and do have effects on dialogue. However, the dialogue is aimless and rarely connects, leaving you with largely featureless models with pasts that have conversations that read almost as randomly generated as the maps. “Good thing you picked me up back there,” “What?” “We should get moving to the next spot,” “I’m tired.”

Parts of this could be salvaged to emphasize a feeling of alienation or despair. The bulbous character models and general apocalyptic scenario remind me how well Playdead mined similar territory for the trauma-laced Inside. Salvaging that tone would necessitate getting rid of the Madlibs dialogue though, which means the personality and past associated with the randomly generated characters is unnecessary. It then follows that the whole idea of randomly generating survivors instead of focusing on a handful of specifics to build a world gets called into question, and so on. Finji would have done well to coalesce the tone of each part instead of letting it spread out as much as it does.

Overland was reviewed using a reviewer-purchased copy of the code on PC through the Itch.io Bundle for Racial Justice and Equality.

The Review

Overland

Overland's attempted dive at presenting a haunted landscape of desperate people trying to survive an unknown menace should have hit the spot in these troubled times. Unfortunately, there is little catharsis, interest, or even cohesion to be had journeying through the USA of Overland. I'm sympathetic to the aims of Overland, but without cohesion it quickly devolves into a tonally varied experience that's more bewildering than emotionally alienating.

PROS

- Emergent gameplay by experimenting with the survival system leads to fun surprises both in enemy confrontation and environmental experimentation.

CONS

- Player characters are pulled in too many directions. They have bare personalities, but rarely distinct design. In a scenario that flattens their existence they have dialogue that feels randomly generated.

- Roguelike structure offers little more than a different starting point.